As with so many aspects of sports performance, there’s no such thing as a one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to training.

Heart rate training theory is like a box of chocolates; there’s a lot of variety available, some methods we love to follow, and others can be like Orange Cremes… best avoided.

With all this extra variety available to us, we can pick and choose the methods that suit our goals and our training preferences, Dr Bryce Dyer highlighted the value of using a training zone system that’s easy to measure, test and track changes, so that you are reaping the benefits.

Many athletes use training zones nowadays and that’s easy to measure, easy to test and easy to track changes, so that you are reaping the benefits.

Whilst weighing up the pros and cons of different training zone systems, Bryce touched upon Low Heart Rate (or Zone 2 or Aerobic Base) Training. It’s an approach that’s gained a lot of attention in recent years as it’s based on the idea that exercising at a lower intensity can improve your fitness and promote fat burning.

On the flip side, the approach has been criticised for being time-consuming, lacking focus on intensity and speed, inducing plateaus and boredom due to the lack of variety.

So, is it right for you? We asked ultrarunner and ExtraMilest podcast host, Floris Gierman, to share his experiences of using low heart training to give you an insight into what it involves…

5 ways to identify your low heart rate zone

The first port of call is to identify your low heart rate zone. There are five methods to calculate your aerobic zone, with the first two requiring no heart rate monitor:

1. Nasal Breathing

Breathe exclusively through your nose during exercise (ideally on a flat course). If it becomes difficult, slow down or take a walk break to lower your heart rate. While simple, this method may not be highly accurate for everyone.

2. Talk Test

Run at a conversational pace and gauge your effort based on your ability to hold a comfortable conversation. Adjust your intensity if it becomes challenging to breathe. This is a straightforward method, but it may vary in accuracy depending on individuals.

For the next three methods, a heart rate monitor is required:

3. Heart Rate Training Zone Calculator

Use a formula based on your resting heart rate and maximum heart rate to calculate your training zone. One potential drawback to this method is that it can be difficult to work out your maximum heart rate. I’ve set up this HR calculator to help you if you do opt to go down this route.

4. MAF 180 Formula by Dr. Phil Maffetone

Subtract your age from 180 and adjust based on your health and fitness profile. This provides a ballpark number for your Zone 2. It takes individual factors into account, but it may not be accurate for everyone.

Here's the calculation:

A. Take 180 and subtract your age.

B. Update this number with the best match of your fitness and health profile:

- For those recovering from a major illness, hospital stay, or are on regular medication, subtract an additional 10.

- If you've been inconsistent in your training or are just getting back into training, or you’re injured, have regressed in training and racing, get more than two colds or flus per year, have allergies or asthma, subtract an additional 5.

- For those who have been training consistently (at least four times weekly) for up to two years without any of the problems above, keep the number (180–age) the same.

- For those who have been training for more than two years without any of the problems outlined above, and have made progress in competition without injury, add 5.

For example, if you’re currently 45 years old and fit into category (c), this shows 180-45=135 beats per minute, without further adjustments.

5. Lactate Test in a Medical Lab

Many Universities and some training facilities have blood lactate testing available as a service; you can also purchase home testing units. Measuring your lactate levels at different training intensities provides specific data on the point where your body begins creating more lactate, and these levels are used to set your heart rate zones. It’s a more costly method and ideally repeated annually to ensure that you're dialled in.

Ultimately, pick a method that you feel makes the most sense for you and keep it simple. You can also choose a few different ones, compare what the outcome is and make your own best judgement.

There might be a bit of dialling in to find that right heart rate zone for you. Once you’ve identified your zone, the game can really begin...

How to start low heart rate training

Here’s Floris’ 5 step plan to get started with low heart rate training:

- Start Conservatively: Begin with a lower training volume and gradually build it up to avoid overexertion.

- Increase Training Volume Gradually: Limit the increase in training volume to a maximum of 10% per week to allow your body to adapt.

- Take Regular Recovery Weeks: Every fourth week, reduce training volume by 30-40% to promote recovery and prevent overtraining.

- Monitor Sleep and Stress Levels: Ensure you get adequate sleep and manage your stress levels to support recovery and overall well-being.

- Personalise Your Approach: Experiment with different methods and adjust your training volume and intensity based on your individual response. Keep a training journal to track progress and make informed decisions.

As you get used to low heart rate training in the first few weeks or months, you’ll likely notice that…

- Within minutes of starting your run, your heart rate will shoot up and you’ll have to slow down significantly or take walk breaks

- you don’t understand why you’ll have to run or walk this slow. Am I really this unfit?

- Other runners you used to beat will pass you.

- People ask what’s going on with you, why are you running so slow?

- Sharing your slower runs on social media is embarrassing because they’re so slow.

- Self-doubt creeps in, and you wonder if you calculated your heart rate zone correctly (most probably you did! If you’re ever in doubt, do the talk test).

- You think you have an exceptionally high max HR. These formulas are a great starting point for almost all athletes, so just learn how to slow down in these initial stages.

- Your first few runs are very slow and you do not feel tired. You feel you could have continued running much longer.

These early challenges can be exacerbated by feeling frustrated at the time and patience required to adapt to the new ‘slower’ training approach. Plus, running at a slower pace or taking walk breaks may be perceived negatively by others, leading to self-doubt or social pressure. Overcoming these perceptions is crucial for long-term success.

Can you still do speedwork?

While low heart rate training forms the foundation, there’s a time and place for incorporating speedwork to improve performance. Here are a few fundamental considerations:

- Gradual Introduction: After several months of low heart rate training, gradually introduce speedwork by slightly increasing your heart rate zone to find an intensity that suits you.

- Proper Intensity: Aim for a 7-8 out of 10 effort level during speed workouts, ensuring you finish feeling like you could have pushed a little harder while still maintaining good form.

- Balanced Training: Avoid excessive high-intensity sessions. Integrate speedwork strategically to complement low heart rate training without overwhelming your body.

- Listen to Your Body: Pay attention to how your body responds to speedwork and adjust the intensity or volume accordingly. Recovery is essential to prevent injury and maximize adaptation.

Is low heart rate training right for you?

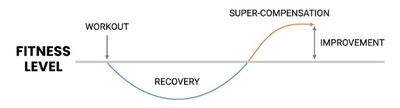

Whether you use low heart rate training or a different model, it’s important to recognise the adaptation curve for your fitness level.

So, after you complete a training session, you need to be able to recover well in order for your fitness level to improve. If that recovery isn’t happening, you’re not going to improve.

Many athletes get injured and burned out when the training volume intensity is too high. Every athlete is different and that’s why it’s not possible to give a minimal amount of training. Some athletes respond well at three hours per week, others at six or ten. I’d recommend experimenting with your training to find the right balance for you.

Journaling can be a powerful tool here. Write down all of the things you’re noticing with the training volume, heart rate zones, and how your body is responding to that in training.

One more thing to add about training volume is, even for me right now with two kids, a start-up, a podcast and a running training program, I simply don’t have the bandwidth to run 60+ mile weeks like I’ve done in some of my peak training. For me, it’s better to run a lower volume, but ensure I’m getting enough sleep so that my overall stress levels are lower.

I’m not going to lie, my stress levels - and I’m sure you might relate - from daily life are already quite high, so this is why it’s a fine balancing game with how much training volume and even training intensity to add. Of course, sometimes you have busier periods in your life when you need to train a bit less or at a lower intensity, and there will be times where you can ramp things back up again.