Precision Fuel & Hydration’s Athlete Support Manager JP recently laced up his trainers for a tough coastal marathon in North Devon. A grumbling from his Achilles heel meant he was forced to ease off the running during the four weeks leading up to race-day and it prompted him to make an uncharacteristic, anxiety-driven decision on the morning of the event.

On the way to the start of the race, JP nipped into a local shop, bought a packet of ibuprofen and popped a couple en route. His thought process went along the lines of ‘why not? They can only help ease the Achilles niggle, surely’.

This train of thought when using painkillers is commonplace among athletes but a growing body of evidence suggests they do more harm than good. Unfortunately for JP, he found this out the hard way…

What are NSAIDs?

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, pronounced ‘n-sads’), like ibuprofen or aspirin, are used by athletes to relieve mild-to-moderate pain and soreness before, during or after exercise in an attempt to keep up with their training and competition demands. The drugs ‘kill’ pain by impeding the body’s inflammatory response (hence the name anti-inflammatory drugs).

The usual NSAID-recommended dose for adults is 1-2 x 200mg tablets taken up to 3 times a day. Sometimes a doctor may recommend a higher dose, but this will only be done under their supervision.

NSAID use is legal and common in sport with significant usage among endurance runners. One study demonstrated that 46% of London Marathon runners planned on taking an NSAID during the race with another highlighting 35-75% of ultra marathon runners ingest them during competition. It follows that the longer the run, the more likely runners are to take NSAIDs.

Runners are by no means the only guilty ones though. Usage rate in other sports has also been shown to be high; 30% of elite athletes on the international stage are thought to take them, with soccer players coming out on top.

How do NSAIDs work?

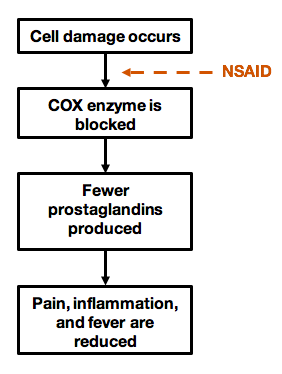

Don’t worry, I’ve kept this part brief. NSAIDs reduce the production of the enzyme COX (cyclooxygenase) which is responsible for producing prostaglandins, a hormone in charge of signalling the inflammatory response. By blocking the COX enzyme, NSAIDs reduce the number of prostaglandins and consequently inflammation, pain and fever are reduced.

What are the negative effects of NSAIDs?

At the end of the day, ibuprofen and aspirin are a drug and like any drug they can have side-effects. This can easily be forgotten because of how easy it is to buy them over the counter.

But, taken too regularly, over long periods or in too high-of-a-dose, the side-effects of NSAIDs become more likely and serious.

In general use (outside of sport), the side-effects of using NSAIDs can include an increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeds (since prostaglandins protect the stomach lining), heart attack, and kidney disease. Side-effects will vary among the different NSAIDs taken and also according to the dosage and frequency of usage.

It’s true that the likelihood of over-the-counter options like ibuprofen and aspirin causing adverse effects is low relative to other, stronger versions of the drug but this shouldn’t lead people into a false sense of security when taking them.

As it stands, the use of NSAIDs by athletes is becoming increasingly frowned upon.

Athletes commonly use them to help meet training targets and competition demands by masking injury and pain. Unfortunately, the counterproductive effects of this to long-term performance isn’t given the recognition it should be by athletes or by some coaches.

More seriously than this, NSAIDs have been shown to contribute to acute kidney injury (AKI) by overtaxing them. This is because NSAIDs impair and alter the kidney’s function (the excretion of water and other waste products). By reducing the kidney’s rate of filtration, they can act as an accelerant to conditions like hyponatremia, rhabdomyolysis and, at the extreme, kidney failure.

NSAIDs also increase the likelihood of gastrointestinal (GI) issues by reducing the stomach’s blood flow and motility. Exercise already causes the body to shunt blood flow away from the GI system, prioritising the muscles (and the skin if it’s warm), but NSAIDs amplify this effect.

A third of runners who said they’ve used NSAIDs reported experiencing an adverse associated reaction and GI issues were the most frequently reported issue.

Lastly, NSAIDs might cause respiratory problems in some individuals. A small percentage of people suffer from aspirin-induced asthma and can feel tight-chested after taking painkillers. It’s thought that the reduction in prostaglandins can result in an overproduction of the pro-inflammatory chemical, leukotriene, which can exacerbate asthma and allergy-like symptoms.

If this is you, it’s something you’re probably aware of and it’s encouraging to see that more athletes are taking the time to learn about the potential effects of NSAIDs (even if they're learning the hard way, like JP!)...

I would say that we’ve been pretty good at educating ourselves, particularly on the use of NSAIDs in competition.

It wasn’t that long ago that NSAID use was rampant, in all endurance sports. They’d take two Advil right before the race or during the race - in fact, for some people it was almost part of their nutrition plan. I would say that was very common in the ultra-running world.

That’s changed nowadays. Athletes are more educated.

If I do find an athlete who has ibuprofen in their race kit, I’ll just take it out of there, throw it away and let them be mad at me.

Jason Koop, ultra-running coach, author and host of the Koopcast podcast

Do NSAIDs improve performance?

Like JP, the common thought process is that the use of painkillers can’t hurt and they might even improve performance.

But neither of these sentiments hold up in the research as data suggests NSAIDs don’t have the desired effect on athletic performance.

A convincing paper measured the influence of ibuprofen during a 160-km ultra in three groups: a control group and two groups taking 600mg or 1200mg of ibuprofen one day before and on race day.

The study found that both groups taking ibuprofen had higher plasma levels of markers for muscle damage. Race times, reports of delayed onset of muscle soreness and ratings of perceived exertion didn’t differ between groups.

What this showed was that ibuprofen may in fact facilitate greater muscle damage without any actual performance gain.

NSAIDs and recovery

Another study found that two-thirds of runners (n=806) admitted to using ibuprofen after exercise, which is a more common prevalence than athletes using it before or during exercise. This perhaps makes perfect sense because post-exercise is when we’re feeling most fragile.

But, it’s at this point that an athlete should be trying to maximise their recovery. So, why do they choose to take NSAIDs?

NSAIDs interfere with recovery. The body’s inflammatory response is imperative in aiding proper recovery by bringing more blood to injured sites. By delaying or impeding the inflammatory response with NSAIDs athletes slow the healing process.

Recommendations for athletes

The recommendations around NSAID use in sport are clear. Using them is definitely a bad idea and they should be avoided during periods of training and competition, especially in ultras.

Research shows ibuprofen use by endurance athletes does not positively affect performance, nor reduce muscle damage or perceived soreness. Rather, it’s associated with elevated indicators of inflammation and cell damage.

Such anti-inflammatory drugs can also exacerbate the risk of kidney damage, cause serious GI problems and, by masking pain, cause greater injury and be highly counterproductive to long-term progression.

The positive news is that the messaging and culture around NSAID use is changing. Events like the London Marathon now advise runners to avoid NSAIDs within 48 hours of the race and education of athletes about their side-effects is improving.

If you ever find yourself in the situation where you’re considering taking painkillers in order to train or race, give yourself a talking to and remind yourself that if you think you need painkillers to get you through, you probably shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.

Rule No.1 is always listen to your body!

This was a lesson that our very own JP learned the hard way.

He suffered badly from 13km onwards in the coastal marathon, experiencing terrible muscle “locking” and severe GI issues later in the day. This was not something he’d ever experienced before in his 15-year history of competitive endurance racing and his event in North Devon ended in a rare DNF at 24km.

I can confidently say he won’t be making the same mistake again (and not just because he’s still reeling from the amount of stick he got in the office for his ill-fated, last-minute decision!).

Further reading

- How not to use painkillers (what JP learned from a self-inflicted DNF)

- Why do my legs hurt so much after some workouts?

- Science of recovery: the importance of food, hydration and sleep

- The 3 R's of Recovery: How to optimise your post-exercise nutrition

- Which recovery tools are worth your time and money?