There are many similarities between endurance athletes and wearable technology:

- They are both durable and long-lasting

- They both constantly iterate and “beta-test” new processes

- They both probably need to recharge more often than they’d like to admit!

As an endurance athlete, you're most likely one of two different people reading this:

- You're thinking about using technology to help you measure your health and performance

- Or (more likely) you're currently using technology to measure your health and performance, and you’re looking to get more value from your device

In both instances - you've come to the right place. I’ve taken a look at five metrics that are worth focusing on when it comes to your performance and recovery…

1. Total Sleep Time

We all know that for both general health and performance, sleep is (or at least should be) a central pillar. Getting sufficient sleep can support recovery, reduce the risk of illness, and improve performance and adaptation. Of course, for endurance athletes balancing high training loads with work and sufficient sleep can be a big challenge.

I’d advise taking a slightly zoomed out approach - is your weekly average between 6.5-8 hours? If it is, then that’s great - and a night or two below this is okay.

If you really can’t sleep long enough at night because of work, training, parenting, etc. - can you squeeze a 30-minute nap in during the day? (I appreciate that this is probably easier said than done!) This can support afternoon or evening training and cognitive performance, but also “top-up” some of your sleep duration to reduce overall sleep need.

For ultrarunners who often run through the night, or the marathoners / endurance athletes who get up at 4am - that’s okay. You can still perform to an exceptional level after 1-2 nights of shortened sleep. These are the days you can add a nap after your race, or if your race is extremely long - maybe even during!

As long as your longer term sleep is sufficient to support training adaptation - don't sweat the small stuff.

2. Resting Heart Rate

Your resting heart rate (RHR) is another fantastic metric that's easy to measure (most wearable tech does a great job of this), easy to understand, and simple to take action from.

I’d expect most endurance athletes to have a low resting heart rate (overnight) - particularly relative to the general population. There will of course be variation between individuals, and contributing factors such as genetics, illness, gender, fitness level, body weight and composition - to name a few.

Generally speaking, lower is ‘better’. But the best way to interpret RHR is that normal = good.

You might see small day-to-day variation (increases and decreases) but any changes around 1-3 beats per minute is within normal range. If you start to see larger changes - that’s still fine, but it likely means you placed significant stress on your system yesterday.

For example, if you do a double-threshold day (double intense session and a likely late-evening session) you might expect to see an elevated RHR overnight. Whilst this increase is nothing to be scared of - it does indicate the need to shift intensity the day after, and likely support recovery through other strategies.

If you see an unexpected increase in RHR (for example, 60bpm - when your average is 50) - I would certainly check in with yourself to see if this is a potential illness.

I’d also recommend monitoring changes in RHR on a successive basis. So, if you see 2-3 consecutive days of a negative trend (e.g. an increase in RHR), then alter your training plan accordingly.

3. Heart Rate Variability

Heart rate variability (HRV) is another wearable-derived physiology metric that can be highly informative.

It's sensitive to global stress (not just exercise), training load, and recovery. It's worth mentioning that most of the research that exists up until recently actually measures HRV in a morning context, where an athlete either lies, sits or stands, and takes a short HRV reading to help determine recovery.

More recently, because of wearables, HRV readings have been taken overnight, either as a whole night average, the first 4 hours of the night, or during deep sleep. I believe that both data points (overnight and morning readings) have value, but in the context of this article I’ll refer to overnight, until more wearables allow people to take morning readings (nudge to wearable companies!).

Similar to RHR, I’d encourage you to become familiar with your normal range. This may be 60ms +/- 10ms (or a range of 50-70ms). Within this range, I’d usually consider that normal day-to-day variation in responses to training, work, and life.

If I saw data points outside of that range, it would certainly be sensible to check in with yourself as to why that is. Is it expected? If not, what may have caused a large change? It doesn't mean that alarm bells are ringing, but if this happens again the next day (particularly a large decrease in HRV), I would be looking at reversing that trend before it has a large effect.

4. Training Stimulus

It's also very important to measure some form of training stimulus, be that distance, heart rate, or ideally both!

You can achieve extremely high recovery scores and have excellent sleep, but if you don’t train, you won’t adapt or be able to perform to the level you want to.

As an endurance athlete, distance (or training volume) is a key driver of adaptation (to a point). Of course within this, it’s important to consider things like elevation, pace, intensity, and of course proper periodisation and planning.

But the larger point being - track some form of training load. It's highly valuable to reflect on your ability to recover from load.

For example, if you accumulate 100km in a week three months ago, and your RHR is elevated and HRV is depressed - a way to monitor ‘progress’ might be that you accumulate 100km this week (same relative intensity) and your RHR is stable, and you see little variation in HRV.

5. Feel

Okay, I cheated. This isn’t a metric from wearables. But it’s hard to leave out amongst all of the tech-derived data. Layering how you feel with data from wearables is the best approach to managing your recovery, training and - at the end of the day - performance.

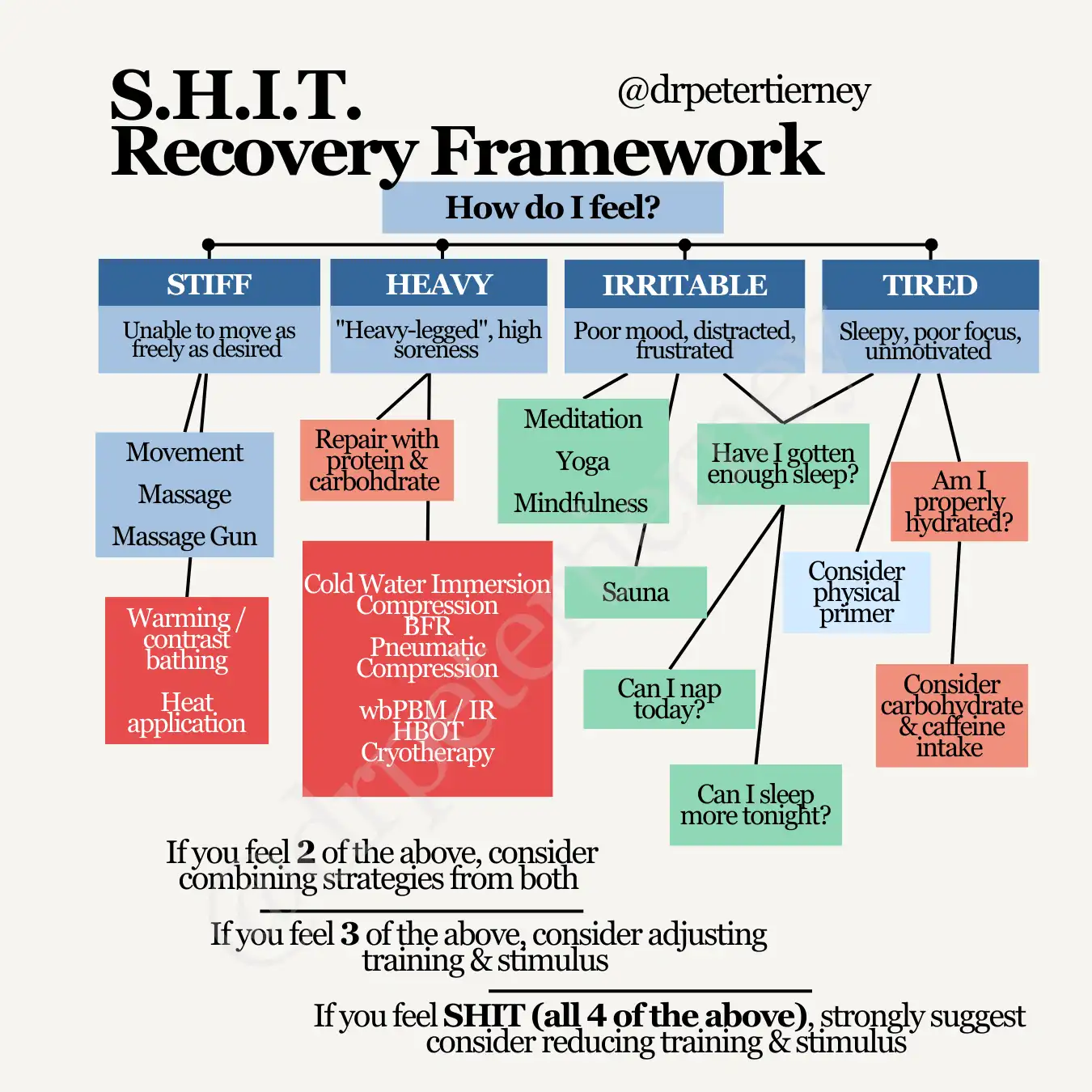

I recommend asking yourself 4 questions each morning - which I have tied into my S.H.I.T. recovery framework.

- How Stiff do you feel? [unable to move as freely as desired]

- How Heavy-legged are you? [heavy-legged, high muscle soreness]

- How Irritable are you? [poor mood, feeling distracted, frustrated]

- How Tired are you? [sleepy, fed-up, unmotivated]

If you feel 2 of these (stiff, heavy, irritable, tired) - consider combining strategies from both sections before training.

If you feel 3 of these (stiff, heavy, irritable, tired) - consider adjusting training and stimulus. For example, reduce the intensity and / or pace of today’s workout

If you feel like S.H.I.T. (i.e. stiff, heavy, irritable and tired) - I would strongly suggest reducing training and stimulus. If feeling really shit, consider today being a rest day or reorganising your week.

Preferably, ask these questions before checking your wearable data if you’re easily influenced.

You can simply interpret these as you need to, but if you are a data-driven person, you can track these on a 0-10 or 0-100 numerical scale and analyse on a weekly or monthly basis.

Layering these subjective questions with objective data is a much more holistic approach to deciding if you need to adjust training intensity, implement specific recovery strategies to prepare you for today’s session(s), and identify which types of workouts produce the largest impact on your recovery.

The metrics that matter

To recap – the main metrics that matter:

- Total sleep time

- Resting heart rate

- Heart rate variability

- Training stimulus

- Feel

The reality is that many people are tracking these, but few are actually using them.

There's a big difference in using the combination of data and feel to benefit your recovery, training decisions and to help measure progress. How many times have you reflected on your last training block, by looking back at logs of training data, perception, and wearable data all together? That practice is extremely valuable to learn from and tweak your next training cycle.

Maybe you learn that your ability to recover after back-to-back days of intensity is poor, based on wearable data and feel. Your learning could be to reorganise your week, or to add in some additional strategies to support recovery between those two days

At the start of this article, I said that endurance athletes are similar to wearable tech – they both constantly “iterate and ‘beta-test’”. I think this process of using important metrics is a prime example of this iterating.

If you're one of the people who uses the data over longer periods of time, to your benefit, and actually applies your learnings to help you – well then, kudos.

If you're not, hopefully you become that person after reading this article!