Working out how much carbohydrate you need per hour is critical if you want to perform at your best during endurance events lasting more than about 60-90 minutes.

You can use our free Fuel & Hydration Planner to give you a ballpark idea of how much you’re likely to need for your next event if you’re not yet sure.

Many athletes, especially those who are aiming to compete at a high level, are surprised by just how much carbohydrate the science and anecdotal reports from elite athletes suggest is both possible and optimal.

Why should you consider training your gut?

It’s fair to say that the carb per hour recommendations for athletes are often significantly higher than many are routinely taking in.

For example, a 2012 study examining carb and fluid-intake rates showed that 73% of marathon runners didn’t reach the relatively moderate recommendation of 30–60 g/hr during racing.

This highlights a substantial gap between their current level of fueling and the desired level they should be aiming for. This gap can possibly be attributed to the fact that some athletes are worried that they won’t be able to ‘step it up’ because of fears that consuming more carb will induce gastrointestinal (GI) distress, something that has been recognised as a leading cause of the dreaded DNF or underperformance in long races.

Whilst GI distress from overconsumption of carbohydrates and/or fluids is definitely ‘a thing’, it’s not a completely insurmountable problem and shouldn’t lead to an unfounded fear of pushing the fueling envelope in pursuit of increased performance.

We’ve written in detail about the science of how the gut can be trained to absorb more carbs and so what follows here is some practical advice and very simple guidelines on how such gut training can be carried out.

It’s important to be clear that this topic is in its infancy as an area of research and that, as such, there are no firmly established gut training guidelines to fall back on. But this doesn’t mean we’re running around without a map or compass!

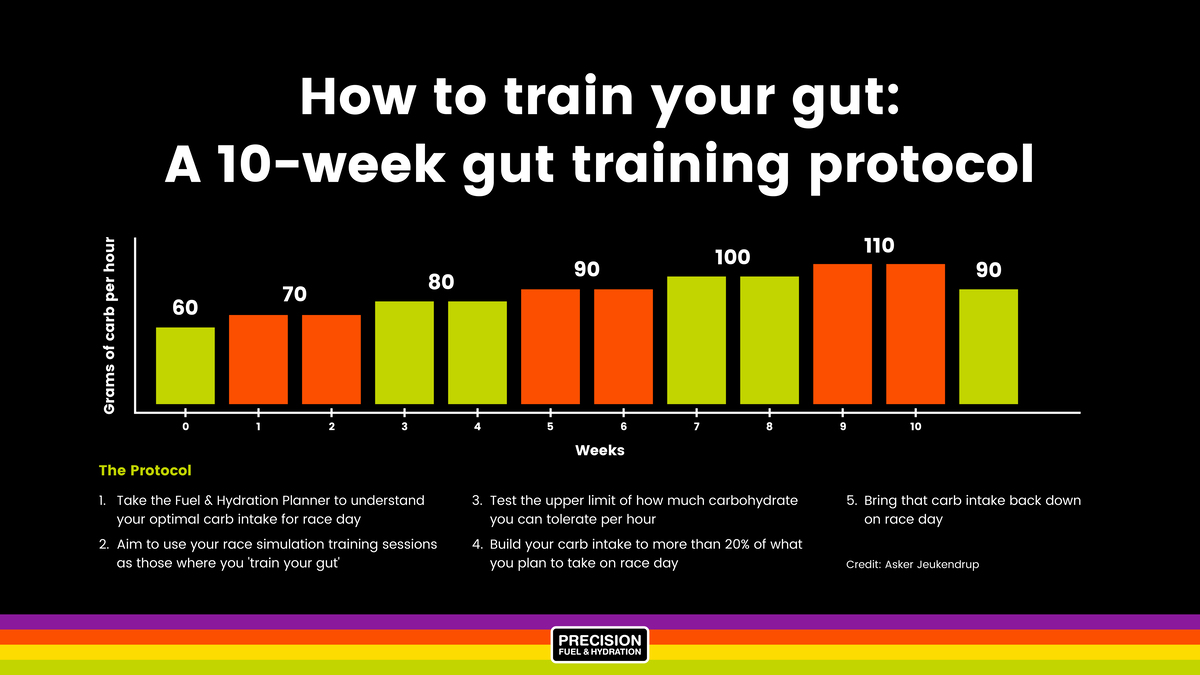

There’s been some very credible groundwork laid in this area by top names in the field of sports nutrition such as Asker Jeukendrup, Trent Stellingwerff and Aitor Viribay, all of whom have a wealth of both lab and field experience from working with athletes at the highest levels, specifically on this topic. A great summary of the available evidence in this area (as of 2017) by Asker can be found here.

Furthermore, as athletes and practitioners ourselves, we have accumulated plenty of practical experiences to lean on too. All of which is a long-winded way of saying that, whilst what follows cannot be described as a 100% evidenced-based consensus, it’s certainly not a stab in the dark and is anchored in the groundwork laid by Asker et al...

Training your gut

Before we get to the specific guidelines, there’s a more general point that everyone aiming to train their digestive system can benefit from and this is around ensuring you’re eating enough carbs in your day-to-day diet...

Carbs in your daily diet

There’s been a lot of interest in the idea of Low Carbohydrate, High Fat (LCHF) diets to improve athletic performance in the last decade or so, but the evidence still points to the fact that fueling high-intensity endurance performance is a job best done by carbs.

By eating an adequate amount of carbs in your daily diet to support your training, you’re already starting to ‘train your gut’ to an extent, because you’re ensuring that your digestive system is up to the job at hand by asking it to process carbs regularly and in reasonable quantities.

On the flipside, if you’re eating a genuinely low-carb or ketogenic diet the majority of the time but you want to perform on a higher carb intake when it comes to racing, it’s worth being aware that there’s a chance this approach may hinder your ability to reap the maximum rewards.

Some people follow a “train low, race high” regime based on the idea that taking in ‘extra’ carbs on race day will give an enhanced boost to performance. But this can be risky and it’s unlikely you’ll be able to tolerate an optimal amount of carbs without GI issues if your body is not properly prepared in advance.

This seems likely to be because the microbiome in the gut (responsible for breakdown of macronutrients for absorption) will not be optimised for carbs if they’re largely absent in the day-to-day diet.

None of this is to say that selectively cycling carbs around your training load, or doing some sessions (or entire days) where you intentionally operate on low carbohydrate availability is a bad thing, per se.

In fact, there are numerous positive metabolic effects and adaptations that can be driven by selectively training ‘low’ on carbs. But following a truly LCHF diet all of the time is unlikely to help you train your gut to be the best carb-processing machine it can be.

The bottom line is that, if racing on carbs is your aim, then by eating a diet containing adequate amounts of them to support your training load - and specifically your hardest training sessions - you’re already taking the first step in training the gut to process carbs on race day.

What can we learn from hot-dog eating competitions?

The ESPN documentary ‘The Good the Bad and the Hungry’ gives an entertaining insight into the weird world of ‘competitive eating’ (where the ‘athletes’ have to consume as much food as possible in a set amount of time). These guys and girls ‘train’ their digestive systems with increasingly demanding portions of food over a period of weeks leading up to a competition in order to increase the capacity they can tolerate.

Whilst at a glance this may not seem all that relevant to endurance sports, what it does prove is that (as is the case with many other aspects of human physiology) the digestive system will likely respond to progressive overload by increasing its capability to absorb calories when pushed to do so.

Although the total amount and types of foods consumed will differ (76 hotdogs during the time it takes to do a very fast 5km run is probably a stretch!), the idea of starting with an amount that’s currently tolerable and then tweaking the quantity upwards on a weekly basis is essentially the same for athletes as it is for competitive eaters.

Gut training guidelines

As has already been stated, there’s no universally defined rulebook for gut training yet, but the following principles offer a useful framework to help you structure a programme in the build up to a key race:

- Work out your ideal or target carb intake (use the Fuel & Hydration Planner if you don’t know this number already), so you know what kind of number you’re aiming for in terms of grams of carb per hour.

- Aim to begin your gut training plan 6-8 weeks before your competition date (possibly even more, if you have the luxury of time).

- Begin by fueling to whatever level you’re confident won't cause you any GI issues in the first week (start cautiously). Progressively increase the amount of grams of carb consumed per hour each week by an amount that will theoretically get you to your target just before your tapering period begins.

- Start taking in fuel early on in the designated gut training sessions so that you can maximise the period of time over which you’re fueling during each workout. This could be as early as 15-20 minutes into a session, which will feel odd for many people used to waiting much longer before beginning to eat.

- Try to practice gut training in at least 1, preferably 2, sessions per week (choose longer and harder sessions, ideally those that most closely mimic the event conditions and intensity). Include ‘B’ and ‘C’ level races if they fall within the build-up period as well.

- Consume the same combination of foods, drinks and sports nutrition products you intend to use on race day in order to flush out any issues you might have with certain brands or specific ingredients. If you’ve not established your intended regime of products yet, then use this period to narrow down your choices.

- Keep very detailed notes on exactly what and how much you consume, and how you feel (energy levels, levels of GI discomfort, overall performance and recovery) for each gut training session, so that any patterns can be analysed.

- Hydrate appropriately alongside your fueling (especially if it’s hot), as dehydration will hinder your ability to absorb calories. If it’s hot and/or if you lose a lot of sodium, don’t neglect that either as sodium depletion will also hurt your ability to process carbs

- Favour carb drinks and gels for the vast majority of your fueling needs if your workouts are less than 2-3 hours or at very high intensity. Incorporate other more solid foods (PF 30 Energy Chews, bars etc) as durations get longer and the intensity decreases (for more on this topic read here).

- Don’t be perturbed if you fail to hit all of your predetermined fueling goals ahead of race day. Everyone is different when it comes to the ability to absorb calories, so as long as you make progress during your gut training cycle it will have a positive effect on your performance.

There's been a trend towards higher and higher carb intakes being reported by elite endurance athletes over the last decade or so. This has stimulated interest in the idea of training the gut to tolerate higher levels of carb intake as a means to improve performance.

Evidence is emerging that athletes can indeed train their digestive systems to become better. Assimilating calories during exercise and doing so in a progressive manner over a number of weeks in the build-up to competition is probably something to take a serious look at if you’re aiming to get the best out of yourself in your endurance races.

Whilst there’s no single roadmap to success with a specific, well-validated gut training protocol, following the steps outlined above is congruent with the most up-to-date advice available and will be a good place to start your own experimentation.