When it comes to working out your fueling strategy for endurance events, understanding how much carbohydrate you need to ingest per hour to sustain peak performance should be your Number 1 concern.

Everything else lags someway behind in terms of importance, so if you’re not sure about your carb numbers yet, consider working those out by using the Fuel & Hydration Planner before you go much further.

Once you’ve got a handle on how much you need (in terms of grams of carb per hour), the next logical question is “what’s the optimal way to get that amount of fuel on board given your specific circumstances?” After all, there are practical and logistical considerations - not to mention preferences around taste - to take into account.

What follows is an attempt to highlight the main pros and cons of each of the 4 major fueling formats commonly encountered by athletes: drinks, gels, chews and bars...

Why the quantity and format of your fuel matters more than the formulation

There’s a tendency in the sports nutrition industry to put a lot of focus on the type of carbohydrate found in different energy products, with many brands making claims that one specific formulation will fuel you better than others, thus drastically improving your performance.

It’s true that different carbohydrates can be absorbed and metabolized at different rates. And it’s logical to assume that these characteristics can be used advantageously in some situations. But it generally only makes sense to consider the type of carbs in your fuel once you’ve already nailed down:

- How much energy you actually need to take in

- What formats will work best in the situation you’re planning to use them in

Why we're focusing on carb-based fuel rather than fat adaptation

There has been a strong backlash against carbohydrate fueling in recent years, alongside the growth in popularity of the idea of using fat as a primary fuel for endurance (i.e. low carb-high fat or keto approaches).

We’ve written about this carbs vs fat debate in detail if you’re interested, so here we’ll just say that the available evidence (and our own experience) still suggests that the best approach to fueling hard endurance efforts is to use adequate amounts of carbohydrate and this is what we’ll focus on here.

The 4 main sources of carb-based fuel for exercise

There are tons of options these days, but most sports nutrition products can be grouped into one of four broad formats: Drinks, Gels, Chews or Bars.

It’s worth saying from the outset that there are no universally right or wrong answers when it comes to selecting a fueling format. The science actually suggests that the physiological differences in consuming drinks, gels and bars are quite negligible. So, personal preference and practical considerations will play strong roles in the decision-making process.

But there are some factors that make drinks, gels, chews or bars (or a combination of them) more likely to be optimal in different scenarios...

Carbohydrate (“Isotonic”) drinks

What are they?

Carbohydrate drinks were the first form of ‘proper’ sports nutrition on the block. They started to gain widespread popularity in the ‘70s as a convenient way to get the critical trifecta of carbs, fluids and electrolytes into your body during exercise to help maintain homeostasis and prevent the decline in performance that comes with substrate depletion or dehydration.

They’re often referred to as ‘isotonic’ drinks and have remained very popular over decades. That’s partly because of the gazillions of dollars of ad spend the likes of Gatorade, Powerade and Lucozade put behind them. But also because they can actually be very effective at helping athletes to maintain performance, when used in the right scenarios.

Most isotonic drinks are formulated as a ~6% carbohydrate solution. That means they contain about 60g of carbs per litre (~32oz), or 30g of carbs per 500ml (~16oz). This has been shown to be something of a happy medium when it comes to delivering an impactful amount of energy, whilst still allowing water to be absorbed relatively rapidly to combat dehydration.

They often contain a small-to-moderate amount of sodium too, which can help to replace small-to-moderate sweat sodium losses.

Carb & Electrolyte Drink Mix actually contains 1000mg of sodium per litre (32oz), about double the amount found in a standard off-the-shelf sports drink, as this can be beneficial for many athletes competing in hot/humid conditions or any other time when sweat losses are high. It’s also closer to the amount of sodium the average athlete loses in their sweat, as we've discovered by Sweat Testing thousands of athletes.

They’re essentially the ‘jack-of-all-trades’ of energy products, as carbs + water + sodium are the basic ‘costs’ of exercising, so replenishing them all to some degree is usually positive in performance terms.

Pros

- Useful for getting fuel into your body for short-to-moderate duration activities (~45 minutes to 2 hours), where the delivery of a steady stream of rapidly digestible energy tends to be the priority

- Require no chewing, little digestion and can be taken in even when you’re breathing pretty hard (with some practice), so they work well even when your exercise intensity is high

- Replaces some of the fluids and sodium lost in your sweat, mitigating the risk of dehydration

These are all reasons why you’ll often see carb drinks being used by fast marathon runners, triathletes on the bike during Olympic distance races, and in team sports like soccer and basketball, where athletes have little time to stop during games to take in more solid forms of fuel.

They can also be useful in situations where most of your calories need to be ingested via a straw, such as when kayaking or hiking with poles in your hands. People who have nervous stomachs before races and really struggle to get solid calories in might find them helpful to augment breakfast calorie intake as well.

Cons

- Unlikely to be able to meet your fluid and electrolyte replacement needs when exercising for more than about 2 hours (especially in the heat), as the volumes required can start to cause GI distress (bloating, sickness, diarrhea etc)

- Reduces the flexibility of your fueling strategy. If you require more fluid and/or sodium and less carbs because it’s a hot day, you can’t have one without the others if relying solely on a drink that contains all three

- Some people don’t like the sweet taste

- Can become very sickly and unpalatable on the taste buds after a long period of ingestion

So, if you’re training or competing for longer than a couple of hours, consider shifting towards using hypotonic drinks containing more electrolytes (or plain water with electrolyte capsules) to meet your hydration needs. And then use gels, chews, bars, or other more solid sources of carbohydrate, to meet your energy requirements.

Energy Gels

What are they?

The first gels appeared in the late '80s as a solution to the problem endurance athletes had of finding a convenient way to carry and ingest concentrated, digestible carbohydrates whilst on the move.

Gels deliver a measured dose of simple carbs in a form that’s lightweight and space efficient. Most contain between 18-30g of carb per serving, with our PF 30 Gel containing 30g of carbohydrate to make it easy to work out the right amount to take per hour.

They’re a kind of halfway house between isotonic drinks and solid fuel such as energy bars and chews. Depending on their consistency, gels often require a drink to help wash them down and aid absorption, which isn’t always practical.

To make it more efficient and easier to hit your numbers when you're aiming for large carb intakes, we've added a few options to our range. The PF 90 Gel contains 90g of carbohydrate and comes in an easy to carry pouch with a resealable top. The PF 300 Flow Gel is a re-engineered version of our popular gel that flow more easily and enables you to get 300g of carb from one bottle or flask. If you prefer your carbs in liquid, Carb Only Drink Mix delivers up to 120g of carb per litre. And like its name suggests, this mix allows you to keep your electrolyte strategy separate.

As a general rule, the more concentrated the gel, the more likely it is that you’ll need to wash it down with a few mouthfuls of water (or a hypotonic sports drink). Environmental conditions and sweat rate tend to play a role as well, with it being easier to consume gels without additional fluids when it’s cooler.

There have been some minor tweaks to the packaging and formulation of gels over the years, but the basic concept is the same today as it was when Ronald Regan was in the White House and gels have become the most popular way to get carbs in during most endurance activities.

Pros

- Easy to carry a large amount of carbs efficiently. e.g. whilst you’d need around 1kg (2.2lbs) of sports drink to get 60g of carbs in, you’d only need ~100g of gels (around 2 standard gels). Useful when you need to be self-sufficient or are travelling light.

- Efficient when your hydration needs are proportionally lower than your energy needs. Like during hard efforts in cold conditions, when drinking enough sports drink to meet your fueling requirement isn’t practical (e.g. in a cool race where you’d need around 30-60g of carb per hour, but you’d only need to drink say 250ml (8oz) an hour). An isotonic drink would deliver only 15g of carbs, but taking 1-2 gels per hour would get you into the 30-60g range far more easily, with less risk of GI distress.

Cons

- Some athletes find they become sickly or unpleasant (“flavour or texture fatigue”) if over consumed, making them less suitable as a primary or sole source of fuel for longer efforts

- Some athletes “just can't stomach gels”, usually because they don’t like the sweet taste. To combat this drawback, the PF 30 Gel has been designed with a neutral, original flavour.

- Not ideal when opening the packets is tricky because you don’t have full use of your hands (e.g. when kayaking or riding downhill on a bike at speed)

Energy ‘Chews’

What are they?

Energy chews take many different forms but are, in essence, similar to energy gels and contain even less water. They look and feel like sweets or candies. They’re made predominantly from simple carbohydrates, like drinks and gels, and they don’t bring any fibre or other macronutrients with them. They’re solid and require chewing which makes them somewhat harder to ingest when you’re working at very high intensities and breathing hard. Some also contain sodium or other electrolytes.

Chews tend to be extremely energy dense, so have a fantastic total carbs to weight ratio, but ultimately require fluids to be consumed with them to aid digestion and absorption in all but the coldest conditions.

Pros

- Because they feel more solid in the mouth, chews can be more ‘satisfying’ to eat than gels during longer races and when working at slightly lower intensities

- They’re a viable alternative for anyone who doesn’t get on well with the texture or taste of gels

Cons

- Not ideal when you’re exercising at a high enough intensity to make chewing and swallowing an issue

- Harder to use when opening packets is tricky because you don’t have full use of your hands

Other than these drawbacks, chews can almost be used interchangeably with gels depending on your personal preference. They’re the obvious choice when energy/weight ratio is the most important consideration.

Energy Bars

What are they?

Energy bars exist at the point where sports nutrition starts to cross over into ‘real food’. Perhaps one of the biggest differences between energy bars and drinks, gels and chews is that many bars contain significant amounts of macronutrients (e.g. protein, fat and fibre) alongside the simple carbohydrates.

Early energy bars (remember the original ‘Powerbar’ anyone?) were, to be kind, pretty bland and could be as effective as any dentist at taking out a loose filling. Thankfully, recipes have improved and manufacturers have become creative in incorporating more 'real food' ingredients into bars to make them increasingly satisfying and palatable.

Pros

- They often contain protein, fat and fibre (unlike drinks, gels and chews), so are generally a lot more satisfying to eat during very long events or training sessions. They can really come into their own a few hours into an ultra, when your body and mind start to crave something more than just simple sugars

- They take longer to digest and absorb, so their energy can be released more slowly, which may be an advantage at lower intensities when maximal rates of carbohydrate oxidation are not required

- They can double up as a handy pre-workout or post-session snack if you’re not able to eat a decent carb-rich meal for some reason

Cons

- Because they’re harder to chew and swallow on the move, energy bars tend to be best suited to ultra-distance events, where it’s possible to eat them because you’re moving at a slower pace. For the same reason cyclists might use more of them than runners - it’s just physically easier to consume bars on a bike than when running

- They tend to need to be washed down with fluid fairly quickly, especially if they’re dry in composition

Energy product pros and cons summarised

| Energy product format | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Carb (“Isotonic”) drinks | + Useful for short-to-moderate duration activities (~45 mins-2 hrs) | - Unlikely to meet your fluid and electrolyte needs over ~2 hrs (especially in the heat) |

| + Require no chewing, little digestion | - Reduces the flexibility of your fueling strategy | |

| + Replaces some of the fluids and sodium lost in your sweat, mitigating the risk of dehydration | - Some people don’t like the sweet taste | |

| Gels | + Easy to carry a large amount of carbs efficiently | - Some athletes find they become sickly or unpleasant (“flavour or texture fatigue”) if over-consumed |

| + Efficient when your hydration needs are proportionally lower than your energy needs | - Many athletes just can't "stomach" gels | |

| - Not ideal when simply opening the packets is tricky because you don’t have full use of your hands (e.g. when kayaking) | ||

| Chews | + Can be more ‘satisfying’ than gels during longer races at lower intensities | - Not ideal when you’re exercising at a high enough intensity to make chewing and swallowing an issue |

| + A viable alternative for anyone who doesn’t get on well with gels | - Not ideal when simply opening the packets is tricky because you don’t have full use of your hands (e.g. when kayaking) | |

| + Excellent energy-to-weight ratio | ||

| Bars | + They often contain protein, fat and fibre (unlike drinks, gels and chews), so are generally a lot more satisfying to eat | - Better suited to ultra-distance events, where it’s possible to eat them because you’re moving at a slower pace |

| + They take longer to digest and absorb, so their energy can be released more slowly, which may be an advantage at lower intensities | - They tend to need to be washed down with fluid | |

| + Can double up as a good pre or post-workout snack |

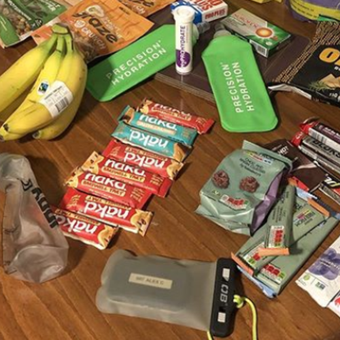

In the real world, most of us will use a mixture of energy drinks, gels, chews and bars to fuel our training and racing, alongside a number of real foods in many cases.

Getting the right amount of energy on board per hour should still be considered your first priority, with the format of that fuel being adjusted to suit the requirements of your situation and your preferences.

Ultimately it’s always going to be better to consume enough energy in formats that you’re happy to eat or drink, rather than trying to force yourself to take in products or foods you really don’t get on with just because others perceive them to be the ‘correct’ choice.

As with many aspects of performance, a healthy degree of trial and error is necessary to get your best choices dialled in, so don’t be afraid to experiment with the guidelines above to find approaches that work for you.

Once you’re confident that you have a good idea of how much carbohydrate you’ll need per hour to perform at your best in what you’re training for, as well as where you’re going to get that fuel from, it might then also be worthwhile considering the advantages and disadvantages of the different formulations of the energy products that you’re thinking of using.

That’s because different types of carbohydrate can be absorbed and metabolized at different rates, which can lead to some ‘marginal gains’ (or even drawbacks) depending on the duration and intensity of your activity.

Further reading

- How much carbohydrate do athletes need per hour?

- Does the type of carb in your energy products really matter?

- How to get your nutrition strategy right for endurance performance

- How does Precision Fuel & Hydration fit in with your wider nutrition plan?

- The 3 R's of Recovery: How to optimise your post-exercise nutrition