As I discussed in a previous article, there isn’t sufficient evidence to support adjusting your hydration strategy based on your sex alone. The optimal approach is a personalised one based on other factors such as your sweat rate, age and environmental conditions.

But, what about energy needs? Do women have different fueling requirements to men? Or is this another area of performance that’s driven more by your individual physiology and circumstances. Let’s find out...

The lack of data from female athletes

A review paper titled ‘Fuelling the female athlete: Carbohydrate and protein recommendations’ was published in the European Journal of Sport Science.

The paper raised a question which piqued my interest. Should female athletes be fueling differently to their male counterparts?

You may be wondering why this question is only being asked now. Surely, in the 21st century, we know whether males and females need to fuel differently?!

Well, no, not definitively anyway…

To set the scene for anyone who isn’t too familiar with the literature on carbs and fueling for performance, the vast majority of research has been conducted on men. This is a general drawback across sport science literature.

One argument for why female athletes have been the subject of fewer studies is that the menstrual cycle and associated changes in hormones makes data interpretation more difficult (I talk about the impact of the menstrual cycle in more depth in my aforementioned piece on female hydration needs).

In a 2017 editorial published in the British Medical Journal, the authors wrote that women have often been excluded from research because they’re seen as “more physiologically variable.”

Historically, women were also left out of exercise science research because many early studies were conducted with the intention of improving military readiness. Since soldiers were traditionally men, using males as the subjects made sense.

For mechanistic studies, (i.e. when a study is simply trying to prove a concept), this argument might have legs, but how are coaches, sport scientists, nutritionists, and female athletes supposed to apply the science to their performance when there are so few trials conducted on a representative population?

When it comes to nutrition and fueling, it's perfectly plausible to suggest that the carbohydrate needs of a female athlete might differ across the different phases of the menstrual cycle, but how are we to know if we never test it and instead continue to extrapolate data from male studies?

It’s against this backdrop that the 2021 EJSS article begins, highlighting this gap in the research. The paper then goes on to collate the studies conducted and draw sensible conclusions based on the evidence and data we have so far. I put a strong emphasis on so far because more studies need to be conducted on female athletes before any water-tight conclusions can be drawn.

The difference between ‘fueling’ and ‘nutrition’

It’s important to recognise that what’s being discussed in this article is ‘fueling’ for training and competition, not day-to-day ‘nutrition’.

The conclusions drawn here about female athletes’ fueling practices and how these may compare to males may be different to those made when discussing whether females’ daily nutritional practices should differ to men’s.

An example of the latter would be that eumenorrheic females (i.e. menstruating females) - especially female endurance athletes - need a greater iron intake than males due to their menstrual blood loss. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is 8 mg/day for males versus a greater recommendation of 18 mg/day for women.

This is one of many examples of differing nutritional advice for males and females but, back to the question at hand, do men and women need to fuel endurance performance differently?

Do men and women have different fueling needs?

Carbohydrates are widely recognised as the key fuel to optimise endurance performance and when it comes to the recommendations for carbohydrate ingestion during exercise, the current advice is no different for males and females.

This is because there’s currently no evidence of differences in exogenous carbohydrate oxidation rate (the rate at which carbohydrate is used in the body) between male and female athletes.

One study looked into this back in 2005, examining the differences in carbohydrate oxidation rate between well-matched male and female endurance athletes. All the women were in the ‘follicular phase’ of the menstrual cycle (i.e. when estrogen and progesterone -the two main sex hormones - are at their lowest and a women’s hormonal profile is most similar to a male’s).

All subjects cycled for two hours at moderate intensity and ingested 1.5g carbohydrate/min (i.e. 90g/hr). As is shown in the graph below, the researchers found that the metabolic response to carbohydrate ingestion, and importantly the rate of carbohydrate oxidation during exercise, was similar between men and women.

But this study used just a single source carbohydrate solution (glucose only) and what remains less clear is whether women have the same capacity as men to achieve superior exogenous carbohydrate oxidation rates when consuming multiple transportable carb mixes (such as the 2:1 Glucose to Fructose commonly found in energy products these days).

A more recent study used highly trained male and female cross-country skiers to assess this. They administered a maltodextrin-fructose blend to athletes at a rate of 2.2g/min (~132 grams per hour) during two hours of submaximal roller skiing.

It was found that carbohydrate ingestion suppressed endogenous (internal) carbohydrate utilisation (i.e. the burning of muscle and liver glycogen stores) equally between the sexes, but that there was a trend for peak oxidation rates to be lower in females (~1.2g/min) compared with men (1.5g/min).

Whilst, at first glance, this is suggestive of a significant difference, the authors concluded that there were no differences identified in substrate utilisation based on sex, whilst also acknowledging that there were some pretty big limitations to their study design. They didn’t control for the phase of the menstrual cycle, nor did they account for the fact that three out of the six females were using contraception.

There isn’t enough information available on this yet, but it’s proposed that females who experience more extreme hormonal fluctuations across their menstrual cycle may differ more greatly from their male counterparts than those with less extreme fluctuations. This is a point made repeatedly in the 2021 EJSS article and by other researchers in this field.

Nonetheless, the 2019 study showed that highly trained female athletes are able to tolerate high doses of carbohydrate during exercise without experiencing performance-inhibiting gastrointestinal symptoms.

Why don’t women appear to differ from men when it comes to fueling?

One of the most common arguments for claiming that men and women should fuel differently is the idea that men may need more carbs because they’re generally bigger and, as a result, must require more fuel. It’s a tempting assumption to make, but one which doesn’t really appear to hold true in practice, or in the scientific literature.

No correlation has ever been seen between body mass and carbohydrate oxidation rate.

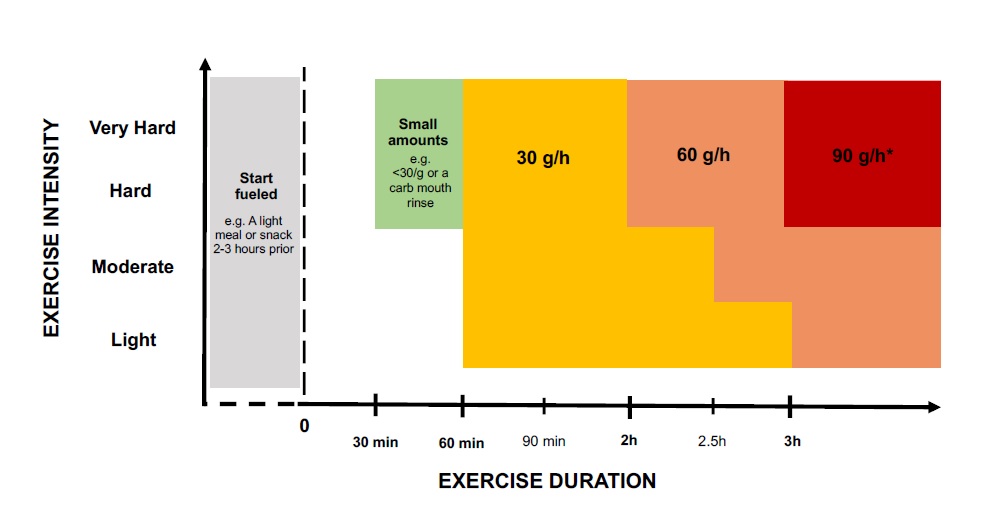

It’s for this reason that carbohydrate intake recommendations during exercise are presented in terms of grams of carb per hour, not per kilogram of body mass (unlike, say, daily carbohydrate or recovery recommendations). Instead, these are dependent on the duration of exercise, as well as the exercise intensity (to some extent) and the goal of training or racing.

This can be an odd concept to get your head around, surely you’ll need less carbohydrate if you weigh in at 60kg (132lbs), compared to the needs of a 90kg (198lbs) athlete?!

Again, the answer is ‘no’. Here’s why...

Ingested carbohydrate is used at a rate in the body that is dictated by the rate at which it can be absorbed into your bloodstream from your intestine. It‘s this intestinal absorption which acts as the primary rate-limiting factor.

Put more simply, if a person can’t absorb this carbohydrate rapidly, they can’t use it rapidly. The evidence shows that athletes have the ability to absorb carbohydrate at similar rates, regardless of their body weight.

In the interests of accuracy, I should point out that the last statement is true for athletes with a body weight range of 60-95kg (132-209lbs). Evidence for athletes with body weights outside of this range is limited and it’s reasonable to suggest that things might be different at the very extreme ends of the spectrum. Again, more research is required!

This point is illustrated in this graph:

There are many reasons why some athletes might struggle to absorb higher intakes of carbohydrate, not least that their gastrointestinal system may not be accustomed to greater loads. To rectify this, an athlete should undergo some gut training in advance of key performances.

Females, particularly those smaller than the average male, may be used to eating less calories day-to-day overall, so they may not be starting the gut training protocol as soon or at the same amount as their male counterparts. The potential is still there though and there's no evidence to show they can't reach the same heights of carb intake through training.

The takeaway is that all athletes, regardless of sex and body mass, have roughly the same potential to absorb and oxidise carbohydrate at the same rate.

Male and female fueling: A real-world example

We work with many elite athletes to help them refine their hydration and fueling strategies for race day. Part of that process involves recording what they consumed just before and during the event, and then crunching the numbers on their sodium, fluid and carbohydrate intake to provide them with feedback to inform adjustments for their next race.

Here is data from two professional long distance triathletes; one male, one female. Note how similar their carbohydrate numbers are…

| Adam Bowden IRONMAN Bolton - 5th |

Laura Siddall Challenge Roth - 2nd |

|

|---|---|---|

| Race duration | 09:08:40 | 08:25:24 |

| Average carb per hour (overall)* | ~75g/hr | ~74g/hr |

| Average carb per hour (bike leg) | ~85g/hr | ~86g/hr |

| Average carb per hour (run leg) | ~83g/hr | ~73g/hr |

| Average sodium per hour | ~518mg/hr | ~138mg/hr |

| Average fluid per hour | ~555ml/hr (~19oz/hr) | ~653ml/hr (~22oz/hr) |

*Includes swim time

Conclusion

‘Should women receive different sports science advice to men?’ is a popular question in sport at the moment. In most cases, the honest answer is ‘we’re just not sure yet’.

It’s positive to see the scientific community recognising the lack of research conducted using women as subjects and slowly starting to correct this. It’s high time that a group making up 50% of the population be recognised appropriately in the scientific literature.

The current evidence suggests that female athletes do not require different guidelines on their carbohydrate intake to men, provided that their total energy needs are met. This is what the research keeps returning to, the importance of consuming enough to fuel yourself as an individual.

The 2021 EJSS articles authors’ overarching recommendation is to “use current recommendations as a basis for adopting an individualised approach that takes into account athlete-specific training and competition goals, whilst also considering personal symptoms associated with the menstrual cycle”.

Which is actually awfully similar to the conclusion we drew about hydration!