Whether you’re tackling your first open water training session, a 5km race, an English Channel crossing, or an ultra-distance swim event, how you fuel and hydrate can be the difference between a strong finish and a boat ride back to shore.

Unlike pool swimming, open water sessions demand more from your body thanks to the longer durations, unpredictable conditions, navigational challenges based on currents, temperature swings, and even sea-sickness. And yet, it’s still common to hear swimmers say, “Do I really need to hydrate? I’m surrounded by water!”.

So, let’s dive in… 🥁

Do you sweat when you swim?

Before we get into your fuel and hydration for open water swimming, let's address a common misconception. It’s often thought that hydration isn’t a big deal when swimming. After all, you’re surrounded by water, right?

But the reality is: yes, swimmers sweat.

During long or intense swims, fluid and sodium losses can add up relatively quickly, even if you don’t feel it because you’re immersed in water. If you’ve ever peeled off your swim cap after a tough swim session and felt fluid running down your face, chances are, that’s not just water.

When your body heats up, the brain’s temperature control centre - the hypothalamus - signals our sweat glands to release moisture (mostly water and electrolytes) onto the skin. On land, that sweat evaporates into the air, taking with it some of the heat we have generated and subsequently helping us cool down. But in water, evaporation doesn’t work as well, if at all. That doesn’t mean you stop sweating, it just means you might not notice it.

In open water, your body relies more on convective heat loss (i.e. transferring heat from your skin to the surrounding water). This means water temperature becomes a major player in how effectively this heat transfer occurs.

When you're swimming in warmer water (or wearing a wetsuit), the temperature gradient between your skin and the water is lower, making it harder to transfer heat away. Your body responds by sweating more in an attempt to regulate temperature - even though that sweat doesn’t cool you efficiently, and you won’t feel it being washed away.

How much do you sweat when swimming?

At the 2024 UltraSwim33.3 event in Croatia, the team and I collected my sweat rate data as I completed the five swims totalling 33.3km over four days...

| Race 1 | Race 2 | Race 3 | Race 4 | Race 5 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swim time (hour:min) | 1:08 | 1:16 | 2:02 | 2:50 | 1:01 | - |

| Average Speed (min:sec /100m) | 1:26 | 1:38 | 1:29 | 1:30 | 1:21 | 1:29 |

| Sweat Rate (L/h) | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 1.26 | 0.98 |

The water temperature was ~19℃ (66℉) for all 5 swims, and as you can see, I lost just under 1L (32oz) per hour on average during each stage of the event. The exception was the final swim, where I was swimming harder, and consequently my sweat rate was higher. This suggests that my intensity had more impact on sweat rate than water temperature, which remained very stable through each swim.

What does the research say?

Scientific research of open water swimmers is relatively limited. However, a 2025 study from Spain analysed sweat rates of elite male and female open water swimmers competing at their National Open Water Swimming Championships. They categorised water temperatures into:

- Cold (<20℃)

- Normal (20-26.5℃)

- Hot (>26.5℃)

Their findings might surprise you, and confirm that not only do we sweat when we swim, but we sweat a lot...

- In hot conditions, 10km swimmers’ average sweat rates were nearly 2L per hour. This resulted in ~3% bodyweight loss per hour for the average ~67kg participant - which is above the 2% threshold for dehydration commonly linked to performance reductions

- In normal water temperatures, 10km swimmers still lost ~1.1L/hour, but this varied greatly depending on swimming intensity

- Sweat rates in more intense 5km races were ~26% higher (~1.4L/h) due to higher output, with the same water temperature

- In cold water, swimmers wearing wetsuits lost just as much fluid as non-wetsuit swimmers did in normal conditions (~1.5L/h). This illustrates how wearing a wetsuit prevents heat loss and subsequently drives up sweat rates, even in cold water

This research tells us that even in cold water, there’s the potential to become dehydrated. And dehydration affects not just performance but also decision-making, pacing, stroke co-ordination, and your ability to regulate temperature. That’s why it’s critical to start your swim well hydrated, and, in longer events, to have a realistic plan to replace fluids and sodium losses during the swim, especially if conditions are warm and/or you're wearing a wetsuit.

How to fuel before an open water swim

You should always aim to start optimally fueled and hydrated, whether you’re racing for one hour or attempting to break the record to swim the English Channel.

Proper hydration supports thermoregulation, muscle function, and energy delivery.

If you're swimming in a wetsuit, in warm weather, or tend to sweat heavily, preload with a high-strength electrolyte drink (e.g. PH 1500) 60-90 minutes before you swim to help you retain fluid and avoid over-drinking.

Avoid chugging lots of plain water the day before and morning of your swim, as this can dilute your blood electrolyte levels, increasing the risk of hyponatraemia (a potentially dangerous drop in blood sodium concentration).

When it comes to pre-swim fueling, even sub-one hour swims use up a decent amount of stored glycogen as our bodies favour carbohydrates as a fuel source during exercise. You don’t need to overthink a carb load before every training session, but gradually increasing your carbohydrate intake 24 hours before a key session is smart.

- Focus on low-fibre, high-carb meals: white rice, pasta, potatoes, carb drinks

- Eat a carb-based breakfast 2-3 hours before your swim to start optimally fueled (e.g. toast and jam, porridge and banana)

- If time is tight, a banana or energy bar 30-60 minutes pre-swim can still be effective. Something is better than nothing

How to fuel during an open water swim

For events shorter than an hour, you generally don’t need fuel or fluid during the swim itself - assuming you've prepared well beforehand.

Fuel & Hydration for swims lasting >1 hour:

When going longer, you’ll still need to start optimally fueled and hydrated, but you’ll also need to consider in-swim top-ups to sustain you for longer. This is important for training sessions, and is vital to achieving your best performance during longer events.

Mid-swim hydration:

- Hydrating during training sessions or races is often logistically tricky. But if your swim is long or intense, fluid and electrolyte loss through sweating still matters, even if you don’t ‘feel’ hot

- The easiest way to access fluids during swims is to complete laps past a pontoon/boat carrying your bottles

- If you’re fortunate enough to have a support kayak or paddleboarder, aim to take on small sips every 20–30 minutes. Try to avoid large gulps of water, as the horizontal body position means your digestive system must work harder in the absence of gravity’s help

Top tip: Occasionally combining your electrolytes and some carbs will help with both fluid absorption and give you extra energy. It also means you have less to do when taking short breaks to get nutrition.

Mid-swim fueling:

Once a swim exceeds an hour, it’s smart to start taking in carbohydrates to maintain energy and avoid dips in focus and performance.

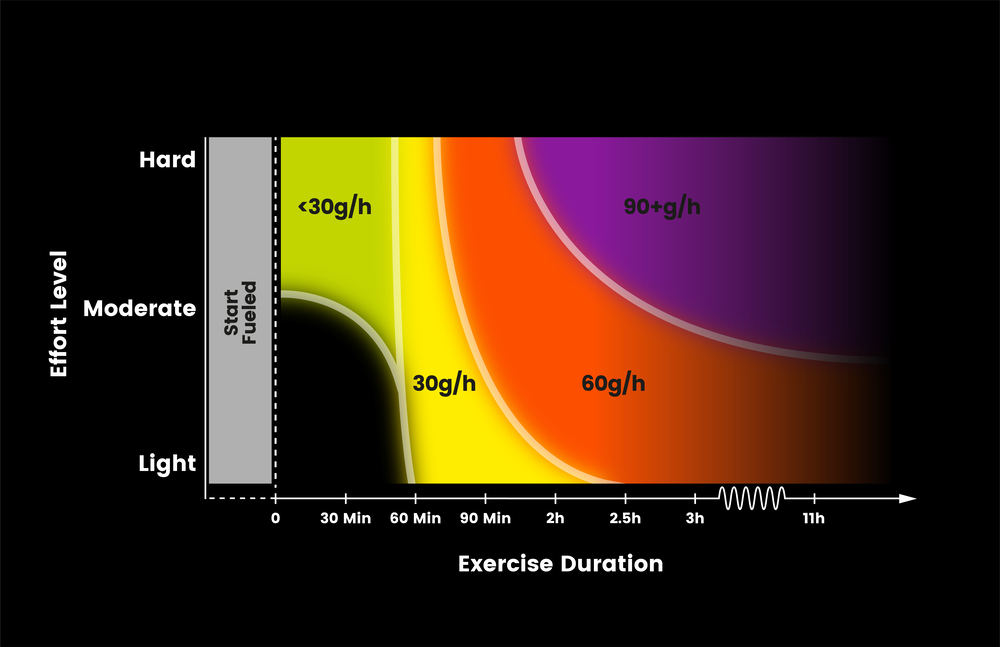

- The general target is 60-90g of carbs per hour (similar to land-based sports) depending on the intensity and duration

- You can see how world-record holder Andy Donaldson has previously hit, and exceeded these recommendations, during his record breaking swims, even finding himself getting hungry despite the high carb intake

- Liquid nutrition is often easiest to take mid-swim (think carb drinks or energy gels mixed in water for quick consumption)

- Some swimmers stash gels in their wetsuit sleeves, clip a small soft bottle to their tow float, or feed from a kayak crew

Practise this in training to avoid surprises on race day. And get a handle on the numbers you should be aiming to hit to perform at your best - the graphic below gives an indication of ideal targets based on the intensity and duration of your swim...

Should your feeds be warm or cold?

The temperature of your nutrition can have a big impact, especially in colder water. Warm feeds are generally better tolerated in cold conditions as they’re easier to digest, make you ‘feel’ warmer when drinking them, and are simply more palatable when you're shivering. They can also be a massive morale boost if you’re feeling cold.

A 2014 review of nutrition considerations for open-water swimming actually found no strong evidence linking warm feed temperatures with significant changes in core body temp.

However, Andy Donaldson found during his Manhattan Island swim that the thermal comfort and psychological resilience of warm feeds is second-to-none. They made him feel warmer, and at the end of the day, if it feels better and helps you keep fueling - that’s performance-enhancing in itself.

If you're swimming with crewed support, ask for warm drinks in insulated bottles or flasks. Even in tepid water, slightly warm carbs and electrolytes can reduce gut stress and keep your stomach happier on longer swims. Just test this in training as some people prefer room temperature feeds over anything ‘hot’.

Along with adjusting your fueling needs, swimming in cold water can actually suppress your thirst reflex, making it more likely you will underdrink, especially if you’re not visibly sweating. Plus, your body works hard to stay warm, which increases your energy (and sometimes fluid) needs even in cooler temps. So adding some warmer fluids makes it more satisfying and palatable.

How cold water impacts fuel and hydration

In cold water, your body ramps up metabolic activity to preserve core temperature. You’re burning more energy to stay warm, even before you factor in the effort of swimming.

This increased energy demand means you should double-down on fueling - especially with carbs - to stay warm and mentally sharp during longer swims. Taking in more carbohydrates than in warmer water swims (especially early in the swim) can help ‘stoke the engine’ and delay hypothermia symptoms like slowed speech, confusion, and noticeable drop-offs in pace.

- Try to feed early and consistently, before you’re shivering or feeling flat

- During his North Channel swim, Andy Donaldson reported improved thermal comfort at just the thought of warm feeds, and found feeding regularly with warm, carb-rich drinks to be the difference between stopping completely, and almost breaking the World Record

Why do I pee more in the cold?

Cold water immersion can trigger something called ‘immersion diuresis’, where blood is redirected from your skin to your core, increasing kidney filtration and making you feel the urge to pee more frequently, even if you're not overly hydrated.

That said, the opposite can also happen: if you’re dehydrated, your body may conserve fluids and you might not pee for hours.

Being aware of both responses can help you triage symptoms on-the-fly, and make a decision to increase or back off the fluid intake if you suspect you’re not peeing, or peeing a lot!

Quick hydration check-in:

- Frequent, clear peeing = likely hydrated, but keep electrolytes topped up

- No urge to pee + dark urine (post-swim) = likely underhydrated

Use this as a guide in long races or back-to-back training sessions to fine-tune your fluid strategy.

How to carry your nutrition

Whether you're training solo at your local lake, racing an event with no external support, or just prefer to go it alone, self-sufficient swimming is completely doable, with the right set-up.

The trick is to try and think like a triathlete meets a minimalist backpacker: lightweight, efficient, practical. You need to carry your nutrition, access it mid-swim, and tolerate it under race conditions, all without making it feel like a hassle or being too disruptive.

There’s no perfect set-up for everyone, but a few tried and tested options stand out:

- Tow floats with storage - can hold small bottles or gels, often with easy-access pockets if you’re treading water

- Soft flask tucked inside your wetsuit – low profile, high utility. Just make sure it doesn’t interfere with your stroke, and practice retrieval mid-swim

- Gels in the sleeve or neckline - old-school and low-tech but effective: stash 1–2 gels in your wetsuit sleeve or under your cap. Just be mindful of sharp edges!

Simplify your nutrition choices

- Carb & Electrolyte Drink Mixes - combine all three of your fuel and hydration ‘levers’ in one place. When used sensibly, this can make each sip of drink tick three boxes in one

- Pre-mixed gel bottles - using products like Flow Gel or gels with a little bit of water in a soft flask are easier to drink and digest mid-swim, whilst still delivering lots of carb per sip

Train your stomach

Eating or drinking while swimming feels weird at first. You’re horizontal, breathing is restricted, and digestion is usually slower. Use your long training swims to test:

- What you need to carry

- How often you will feed (aim for every 20–30 mins if going long)

- Where and how will you stop (Tread water? Quick backstroke break?)

The more automatic your strategy feels, the less likely you'll be derailed by nutrition issues when it matters most.

Key takeaways

Whether you’re swimming short or long, warm or cold, getting your fueling and hydration right can make all the difference.

Here’s what to remember:

- Start well fuelled and hydrated

- Swimmers sweat – even in cold water

- Colder swims = higher fuel needs

- Watch your pee habits

- Fuel & hydrate during long swims

- Test your plan in training

- Going solo? Keep it simple

If you need help dialling in your open water fueling and hydration plan, book a free one-to-one Video Consultation with our Athlete Support Team to discuss your strategy.