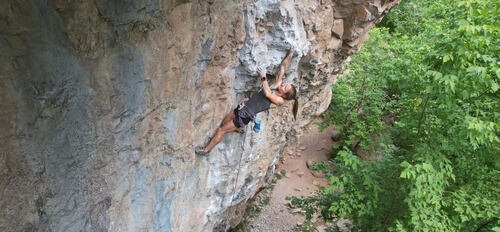

I’ve found my edge as a runner through something that, in theory, should only detract from my running prospects. I didn’t even have running prospects until recently. Climbing came first, while running only served to give me just enough cardiovascular fitness to make it through the hike to the crag without dry-heaving.

But the miles crept up on me. Somewhat unintentionally, casual laps around the neighborhood turned into getting lost for hours on the trail. I went for as long as I had thoughts to fill the time or ran out of water, whichever came first.

There’s a lot more structure to it these days, but my main motivation for running is that it gives me the mental space to think about everything that I can’t touch. Whereas climbing gives me the mental focus to think about nothing but what’s directly under my fingertips.

I wasn’t willing to give either of those up once I’d had a taste, so I decided to experiment with balancing both. Thus far, I’ve hit major milestones including a podium finish at the Leadville 100 and sending 5.14 less than a month later.

The experiment is still ongoing...

The training theories in both sports are unique to each one but don’t really show any overlap in research. But I’ve become my own test subject…

I’ve decided to keep exploring my limits in both until I hit a wall. There’ve been a few speed bumps so far, but never a full-blown barrier. I’ve noticed more benefits than drawbacks to the duo. I’ve only been running for four years, and at a high level for less than half of that time. I credit my climbing background for drastically shortening the learning curve. Endurance athletes can stand to learn a lot from a seemingly irrelevant sport like climbing.

At the risk of spilling my secrets, these are some of the physical and mental crossovers that have helped me - quite literally - hit the ground running...

1. Propulsion

Runners who do anything related to their upper body in the gym are a rare breed. The sport has started to recognize the importance of building strength, but mostly in terms of injury prevention, especially for distance runners who aren’t trying to grow their fast-twitch muscle fibers. Squats and deadlifts? Maybe. Anything above the waist? Hard pass. That’s just extra weight to slow you down, right?

Wrong. I have much more upper body muscle than most around me on the start line and it’s only done me favors (well, except for the chafing…but that’s a story for another day). Legs may be the primary driver for runners, but they’re not everything and they won’t last forever - especially if you don’t supply them with any backup. Strong shoulders, arms, and core muscles take some of the onus off of the legs with every swing so they don’t have to work as hard. That’s particularly helpful toward the end of races and long efforts when your overworked hips, glutes, and quads inevitably start to give out. The upper body can share the burden of propelling you forward.

Plus, if you’ve ever watched exhausted ultrarunners cross the finish line looking like the Hunchback of Notre-Dame, you can likely blame it on a weak core. That’s neither an efficient nor safe position to be in for long. Plenty of post-race injuries stem from slipping into poor form. A stable core makes it easier to keep good posture even when fatigued, which reduces the risk of injury during and after an all-out effort.

It took a while for my legs to get the hang of running far and fast over hilly terrain. But in the meantime, the strength I’d cultivated in my upper body for climbing made up a good chunk of the difference. Powerful pulses with my arms continue to play a role in both driving me up steep climbs and keeping me stable on harrowing descents. Keep arm day on your strength training schedule to get the same benefit.

2. Stability

Speaking of stability, climbing has more to offer endurance athletes in that department besides ripply biceps and washboard abs (but hey, perks are perks). It might go without saying, but climbing well requires balance. What might not be so obvious is what it takes to cultivate such balance. There’s just as much strength involved as skill.

Depending on microscopic dimples of rock is a full-body endeavor that recruits everything from your toes to your traps. Balance comes down to effective muscle activation more than anything else. Climbers need to be able to fire up muscles that most people don’t even know exist in order to find stability in tenuous positions on the wall.

So how does that ability apply to endurance sports like running? Yeah, we use both legs to run - but never at the same time. Runners are in a constant state of flux, shifting weight from one side to the other with every step. The more haphazard that shift, the less efficient the movement and the greater the risk of injury. That only becomes more pronounced on trails where the terrain gets increasingly fickle.

A little bit of balance goes a long way for runners. You can save yourself a ton of wasted energy, not to mention the heartache of a sprained ankle or an overcompensation injury like the dreaded IT Band Syndrome. Spend more time on one foot. Get to know the miniscule muscles in arches, calves, thighs, and hips that contribute to stability. You’ll run faster, farther, and safer for it.

3. Power

Climbing, especially at my size, involves some serious air time. My 5’1” frame can’t span the same distances as my taller friends. Sometimes it’s a legitimate deal-breaker. But rather than write off every far-off hold as “too reachy”, I’ve learned to get jumpy instead.

It’s still not my strong suit. But since it’s a weakness of mine, that means I’m constantly working on building power for moves that test the limits of my wingspan. Most of that power actually originates in the legs. Those larger muscles can generate more dynamic energy than the comparatively smaller muscles of the upper body.

When it comes to running, that kind of power generation through the legs translates to a bouncy, bounding stride that’s more efficient at higher speeds than a heavy, plodding one. You can cover more distance with less energy by springing up quickly from the ground. And since what goes up must come down, training to jump also involves training to land. Practicing light landings helps runners better absorb the forces of impact with the ground, and channel that energy right back into the next step.

Make friends with plyometrics. Get explosive with box jumps, split lunges, burpees, jump tucks, and bunny hops. Focus just as much on the down as the up to get the full benefit.

4. Pacing

I’d wager that climbers spend almost as much time resting on climbs as they do actually climbing. Every time we reach a halfway decent hold, you better believe we’re milking that opportunity to shake out the pump from our arms and psych ourselves up for the next section. Completing a hard climb often depends more on strategic resting than brute strength.

Climbers use rest stances to pace their efforts on a route. We’ll move quickly through a series of challenging moves just in time to reach a restful position before the tank runs dry. It takes a high level of body awareness to know just how much energy we can expend between rests without burning out, and how long to stay in each rest to recoup as much energy as possible without letting the fire die.

That’s exactly where plenty of endurance athletes struggle, especially on race day when excitement can cloud your better judgment. Who among us hasn’t gone out too fast at least once and regretted it as soon as the dreaded bonk set in 20 miles later?

It’s not as simple as just starting out slower than you might want to in the moment. Endurance athletes can rest strategically along the way too. Use mile markers, landmarks, and aid stations to break your route into manageable sections. Take those opportunities to check in with where you’ve been, where you’re going, and how you’re feeling. How hard did you push through the last section? How hard are you going to have to push through the next? What do you need to recover well enough from the last to give it hell in the next?

5. Efficiency

Climbing is all about taking the path of least resistance. We scan a sea of holds for the most efficient line and have to act on those observations almost instantaneously. Snap judgments end up carrying a lot of weight. Make the wrong choice and you’re left hanging on the rope before you even know what happened. With that in mind, climbers get good at making smart choices in a split second to keep from sabotaging the send.

Steal our tactics and practice “route-reading” on the fly. Don’t just blindly tackle the path ahead without consideration for the details. Run smarter, not harder. Take note of potential obstacles. Practice plotting the path of least resistance around them. Sometimes you can actually save both energy and time by adding a few steps instead of forcing your way through.

6. Control

Climbs are rarely linear. A route will often make a stark transition from an easy jug haul straight into a heinous crux that demands every ounce of your physical and mental energy without so much as a head’s up.

Hang around a climbing crag long enough, and you’re bound to hear some interesting noises come out of our mouths: grunts, sighs, shrieks, an expletive or two… and it’s not just for show. They’re all ways of leveraging the breath to control effort and output. Long, slow exhales calm the nervous system down for delicate moves; sharp, powerful exhales amp it up for explosive moves.

Endurance athletes should consider doing the same.

- Rely on the breath to swiftly regulate intensity

- Switch into a higher gear on demanding terrain with a strong exhale that audibly expels the air from your lungs in one short breath

- Wind down to conserve energy on easier terrain with a gentle exhale that slowly releases the air over the course of a few seconds

Even though it’s easier for an endurance athlete to tell when sh!t’s about to get real (like when you see a massive hill looming or a horizon line signaling a steep, rocky descent ahead), breathwork can help with the transition.

Running and climbing might not seem like they have much in common at first. In many ways, they don’t. That’s part of the appeal for me. I appreciate the opportunity to move my body and engage my mind differently. But a few key crossovers from climbing have given me a leg up (pun intended) as an ultrarunner. Now, climber or not, you can reap the benefits for yourself.